Searching for the Cause

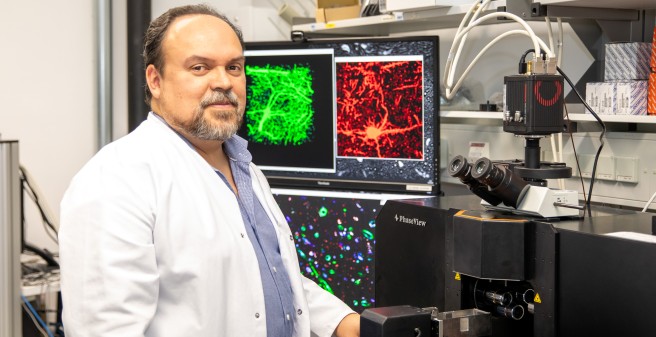

With a unique research base from his Colombian homeland, Dr. Diego Sepulveda-Falla is seeking to discover the causes of Alzheimer's disease, and to guide the research on Alzheimer's in new directions.

Text: Julia Dziuba, Photos: Eva Hecht

It was not his initial intention to pursue research on the origins of Alzheimer's, Sepulveda-Falla says on a rainy summer day in his office. He originally had other plans. Even working in Alzheimer's research in the first place was “a coincidence”. Sepulveda-Falla is used to changing his plans and starting over. In Medellín in Antioquia/Colombia he first studied graphic design, then industrial design, and then he dropped out because it felt unfulfilling. In retrospect, he says that we wanted his job to have a more profound meaning and purpose, which led him to medicine. But during his studies, he realized that the everyday routine in clinics was not for him: "That's one reason why I chose research." He recounts how, as a student, he arrived late to an anatomy seminar and saw the large projection of a brain in the darkened room—"it was love at first sight," he says. Sepulveda-Falla focused on neuroscience and, while still a student, his journey brought him to Dr. Francisco Lopera’s research group. For about 15 years, Lopera had already been researching a population of approximately 5,000 people in Medellín with the so-called Paisa mutation—a particularly severe and early-onset form of Alzheimer's. Carriers of the mutation already develop symptoms of the disease when they are mid-40’s, and die several years later.

Sepulveda-Falla helped taking posthumous brain tissue samples from patients who had made their brains available to Lopera and his team. When a research collaboration with the University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf (UKE) began, Sepulveda-Falla brought some tissue samples to Hamburg in 2008. He says he was allowed to choose his research location. He knew close to nothing about Germany, which was part of the reason for his decision: "Germany sounded more like an adventure." He was then thrilled with Hamburg, he says; with its architecture, the Alster, and its green spaces and parks, it is one of the most beautiful cities he knows. But he no longer has time to go rowing on the Alster in his free time. He has a family, with twins in nursery school, and for the past five years, he has been leading an eight-person research lab at UKE, with the goal of no less than advancing a change in the direction of Alzheimer's research.

"My research focus has shifted," he says. When Sepulveda-Falla came to Hamburg, the prevailing assumption in Alzheimer's research was that the accumulation of the protein beta-amyloid was the most promising approach for potential treatment strategies. Amyloid-beta is a fragment of the protein APP. When certain mutations of APP and other genes occur, amyloid-beta accumulates, which can merge into large plaques—a characteristic of Alzheimer's, as this process could cause the death of nerve cells in the brain. But answering the question of Alzheimer’s origin and treatment is not as simple as research suggested at the time, Sepulveda-Falla admits, self-critically extending this observation to himself. There won’t be a magic pill that will cure the disease as if by waving a magic wand; personalized therapy approaches are more likely to occur.

His research lab also approaches its work with a focus on the individual level. The scientists first look for singular gene effects on the basis of 125 samples from the brains of persons with the Paisa mutation. Recently, attention focused on two individuals in the population who had shown symptoms of hereditary Alzheimer's disease 25 to 30 years later than the average. What had protected them from an earlier onset of the disease? Sepulveda-Falla and his team, as well as colleagues from the University of Antioquia and Harvard Medical School, were able to identify gene variants in different proteins, such as the so-called APOE Christchurch and Reelin-Colbos mutations, which have a protective neuronal effect in the context of Alzheimer's. Similar effects were confirmed in follow-up studies for larger populations. Also, the entorhinal cortex, a key brain region for learning and memory, appears to benefit from the protective effect. A breakthrough?

In any case, it is becoming clear that there needs to be a shift in research, says Sepulveda-Falla. In his quest for a fundamental understanding of Alzheimer’s, he would like to find out how it is truly defined. Its pathological effects in the brain are comparable to the destruction after a war: "All you see are the remnants of a catastrophe." This pathology is confused with the disease mechanism: "What we've been doing for the last hundred years is searching for clues among these ruins to figure out what happened." In his view, this is not the right approach—by the time symptoms of the disease become noticeable, it is far too late: "Whatever causes Alzheimer's, happens 30 years earlier." Identifying this original event is essential for us to subsequently halt the disease mechanism: "Only then we will be able to make a difference."